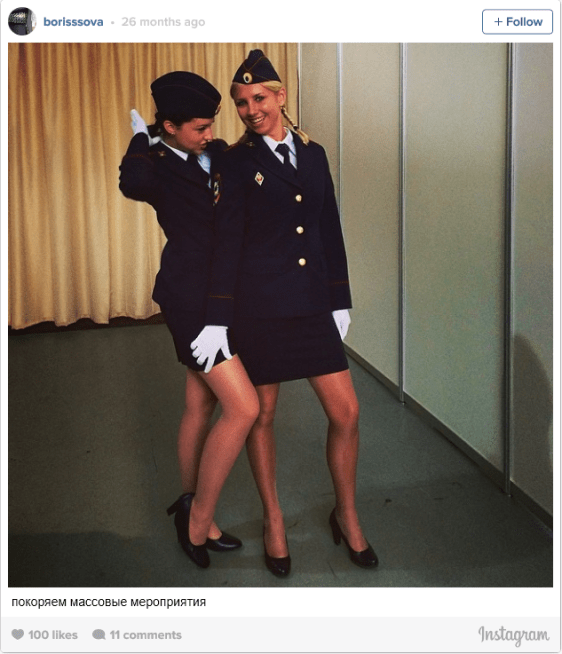

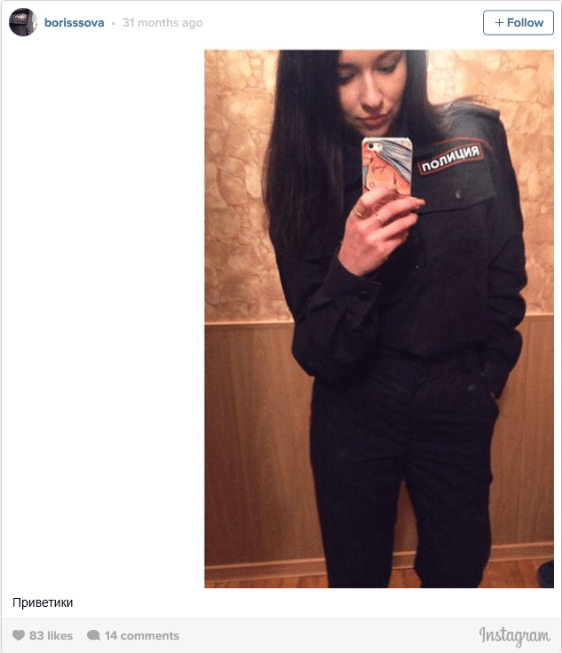

Three years ago, Olga Borisova decided to join the St. Petersburg police force. Eighteen years old and, by her own description, a petite, fashionable young woman, she wasn’t your average cadet.

After a little more than a year, she quit, and has since become an active member of the Russian democratic opposition.

Earlier this month, Borisova wrote for the website Batenka.ru about her experiences as a police officer.

RuNet Echo is publishing her text, translated into English, in three parts. This is the final installment. You can read her full story here in Russian.

March 2014 came along, and I left the city for a TsPP (professional training center). When I got there, the men in charge made my drunk, insecure bosses look like loving parents.

Future cops from all over the city are made on the parade grounds. You’ve got to look sharp. The man in charge walks up and down the line with his hands behind his back. They assign you courses and they put you into a squad. You get a schedule of classes. On the one hand, the first day is a lot like the first day of school. Everyone looks good, and everyone is a bit nervous. On the other hand, it’s probably what the first day in the army looks like, too. They select the squad leader from the more experienced staff. Our leader was a man named Vitya. He was plump as a pastry.

The whole experience was pretty fun. There was flirting and there were flings. You made friends and passed notes in class. It was all like being in school. Police academy. Firearms training, drill instruction, tactics in maintaining public order, physical training, legal training, medical training, psychological training. In psychology, we once watched the film “The Major” with Yuri Bykov. Some future riot police officer brought it in on a flash drive.

Morning formation, daytime formation, and evening formation. Lunchtime formation. Marching in lockstep. If somebody in the squad “stepped” badly, the whole squad could be left to march until eight in the evening. That’s how they developed discipline.

Don’t ask questions. Just take orders.

You’re not allowed to paint your nails. You’re not allowed to wear jewelry. Once, I showed up to formation with long press-on nails painted aqua blue. Then the course officer somehow noticed me, a short woman four rows back, as if he could sense my panic.

“Junior Sergeant Borisova!”

“Present!”

“Step forward!”

“Yes sir!”

Coming to the front of the formation and marching two steps forward, like they taught us, I turned and faced the squad.

The colonel then walked up to me, grabbed my hand, and showed my manicure to everyone in class, saying “What is this?!”

The whole class waited to hear what my punishment would be.

I didn’t flinch, making “big eyes,” I turned to him and said, “But, comrade colonel, it’s the color of the uniforms.”

I watch as a hundred police cadets tried to contain their laughter. The colonel was in a good mood, and he liked my joke. He smiled and said, “I expect those to be gone by tomorrow.” And I answered, “Yes sir.”

But there were also times when he spent a half-hour chewing out somebody in front of everyone for one little mistake in their uniform. Showing everyone who’s boss.

And so, well after all your classes had ended, you spent 40 minutes standing still, in melting heat or freezing cold, and you wait for the colonel to finish his ego trip, so you can go home.

During my training, one of the cadets lost his mind. He was living in the barracks and one day he just didn’t get out of bed and come to class. First, the squad and even the squad leader tried to rouse him. Then the colonel came. And then the center’s director. But even then, the guy just stayed in his bed silently, staring up at the ceiling. They took him to a hospital, and then to a mental ward. They dismissed him for health reasons, and now he’s registered with a psychiatrist.

His story turned out to be pretty cliché, too: his father was a police officer, and he insisted that his son follow in his footsteps, to keep up the family trade. The guy had no wish to be in the academy. In our class on tactics in maintaining public order, he got four straight D’s. He worried that he wouldn’t live up to his father’s hopes, but being a cop wasn’t the life he wanted for himself.

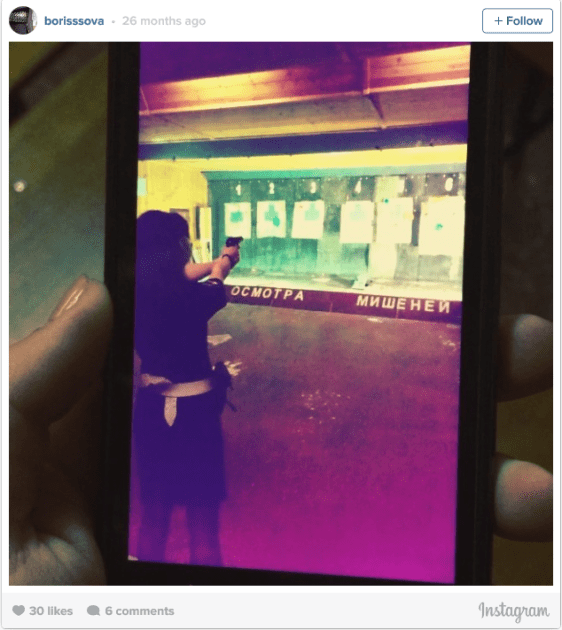

I liked the practical exercises in firearms training the best. I was a good shot.

Once the colonel-instructor looked at my target, and called to the riot police cadets, who liked to flaunt their skills more than anyone, and he said, “Look over here and learn something, boys!”

Apart from being able to handle a weapon and knowing the necessary laws and regulations, the most important professional skill you’re taught is obedience. I was struck by how they rewarded the dumbest guys who couldn’t recite a single criminal statute, just because they were loyal to the bosses—for ratting out other cadets, for being ready to carry out any order, for “offering to be of service.”

Classes go for four months, then there are final exams, then you take the oath, and poof now you’re a certified cop. And you head back to your own precinct.

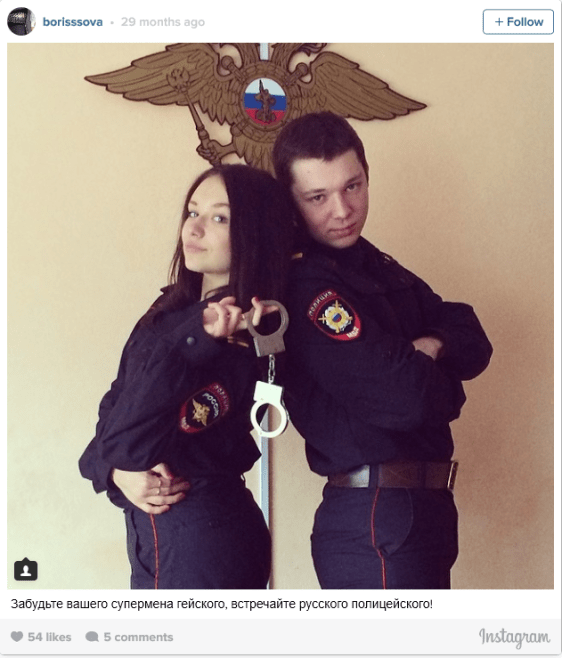

In the meantime, a lot of good people had left. But there were still some, like my partner Andrei, who never took a bribe, who did his work honestly, but the captain saw him as weak and he saw himself as strong, taking every opportunity to humiliate him. I worked with Andrei most of all. We’d talk often, and I’d ask him—a 23-year-old young man, who’d aged nearly a decade after just five years on the force—why he put up with it all.

“Eh, big deal. That’s the cost,” Andrei told me.

That was the moment I understood that “professional deformation” isn’t just developing the habit of noticing anyone walking around with open cans of beer (I still can’t turn it off); it’s also learning to “swallow” personal injustices and later injustices aimed at others. Those who don’t learn to swallow it don’t last long. And [President Medvedev’s] police reforms, because they added to the number of inspections, gave cops like my boss even more levers for filtering out the “defiant” ones.

To summarize, here’s the conclusion I drew two years ago: the people on the force can be divided into two categories: rats and wimps.

My story in the police, which lasted one year and three months, ended with my realization that I didn’t want to become a wimp. Many people observe the injustices perpetrated by the authorities, but too many people don’t understand how much injustice goes on inside the system itself on a daily basis.

So I quit.

***

Two years passed, and I found myself in Montenegro, working on an art project together with my friend Masha Alekhina [of Pussy Riot]. By now, I had some experience doing election work for the opposition; I’d helped with dozens of trials against opposition activists and artists; I’d put together my own political art performance; and I’d helped organized a signature campaign to help my friend in the opposition get on the ballot.

I stepped onto the balcony, and fired up my iPhone screen. I had a new message on Vkontakte. It was from “Sweetie.”

“Olya, please forgive me for everything. If you’re ever in Petersburg, come visit, and I’ll tell you the news about how I’ve got my own office now. They got rid of the precinct chief, and now it’s that other one. And remember Yulia from criminal investigations? They’ve brought two charges against her. It’s half her own fault, but, you understand, I can’t discuss the details here.”

I looked at the screen and saw that there was still more.

“Every day, I go to bed and think that today there was a little less bad than good. Of course, every day doesn’t turn out that way, but still. And if you’re mad at me for any reason, I’m sorry,” he wrote.

“I don’t get offended that easily,” I answered, and I dropped the phone back into my pocket.

This text was translated from Russian by RuNet Echo’s Kevin Rothrock. Read the first installment here and the second here.

![]() Written by Olga Borisova

Written by Olga Borisova