5 May 2016

Get the report

Federal Spending on Postsecondary Education.pdf

Get the data

Postsecondary Education – Data.xls

Interactive Chart

Summary

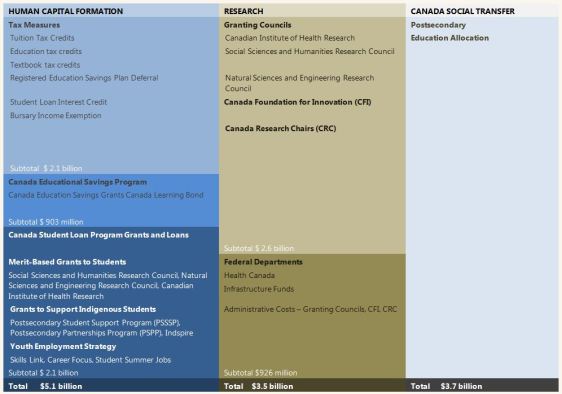

Table 1: Federal Postsecondary Education Expenditure by Major Stream, 2013-14

This report analyzes federal spending on postsecondary education in Canada over the past 10 years; and, where possible, analyzes the distributional impacts of federal programs. It also provides forward projections to 2020-21 taking into account recent Budget 2016 announcements.

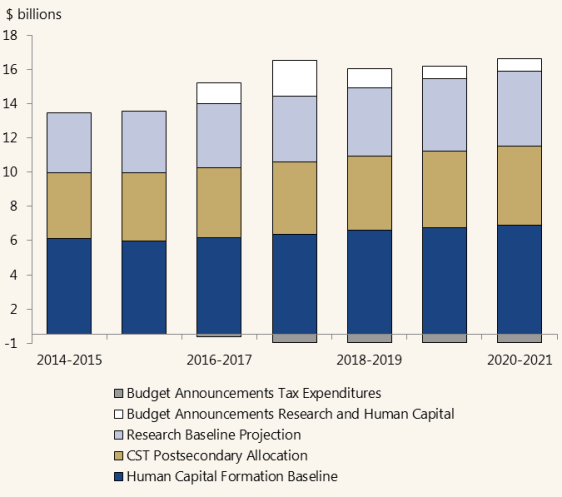

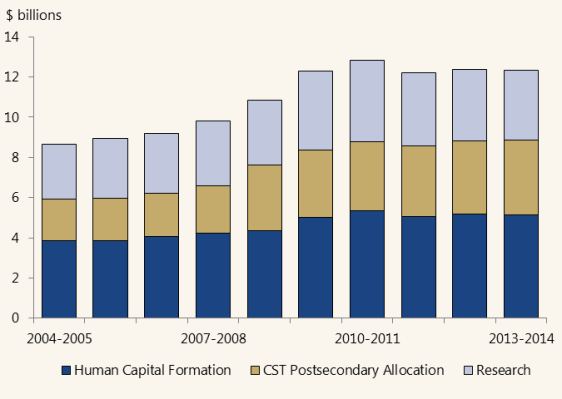

In 2013-14, total federal spending on postsecondary education reached an estimated $12.3 billion. This represents a decline from its peak of $12.8 billion in 2010-11. Over the past ten years, the greatest growth occurred in spending that supports human capital formation and the Canada Social Transfer (CST).

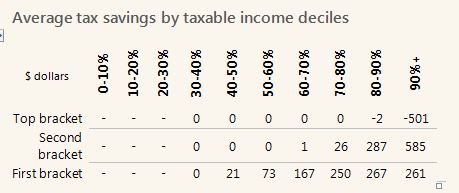

PBO estimates that roughly 60 per cent of postsecondary students belonged to higher-income families (that is, the two highest after-tax or disposable income quintiles).

Increases in federal funding targeted towards human capital formation have primarily benefited these families. This was due to a growing share of federal support provided through the tax system and the Canada Education Savings Program, Registered Educational Savings Plans.

Figure 1: Federal Expenditures on Postsecondary Education, by Area of Focus

Taking into account recent Budget 2016 announcements, PBO estimates total federal spending on postsecondary education will exceed $15.7 billion by 2020-21. The re-allocation of education and textbook tax expenditure savings towards increases in student grants, loan repayment and student employment assistance (announced in Budget 2016) will likely make postsecondary education more affordable for some Canadians. These measures will not, however, significantly change the distribution of total federal spending on postsecondary education.

Figure 2: Expenditure Projections – Total Federal Expenditures on Postsecondary Education