Get the report

Budget 2016: Key Issues for Parliamentarians.pdf

Summary

The presentation of the fiscal plan

The Government has made changes to the presentation of its fiscal plan that have made it more difficult for parliamentarians to scrutinize public finances.

- The Government did not provide detailed tables that identify the impact of changes to its adjustment to the private sector forecast and the effect of policy measures.

- Budget 2016 shortened the time horizon of cost estimates from 5 years to 2 years.

- Key fiscal information is being released outside of the budget and Fall Update with no reconciliation between the main documents.

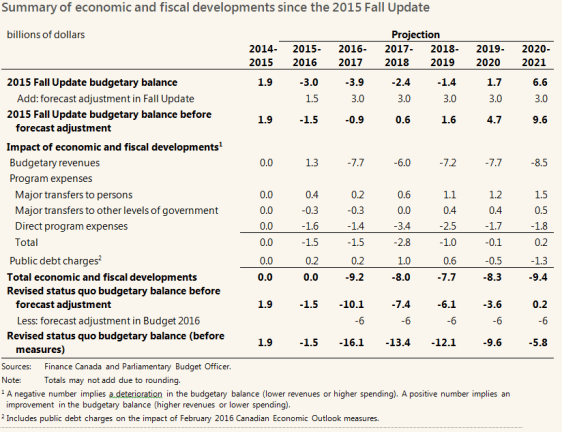

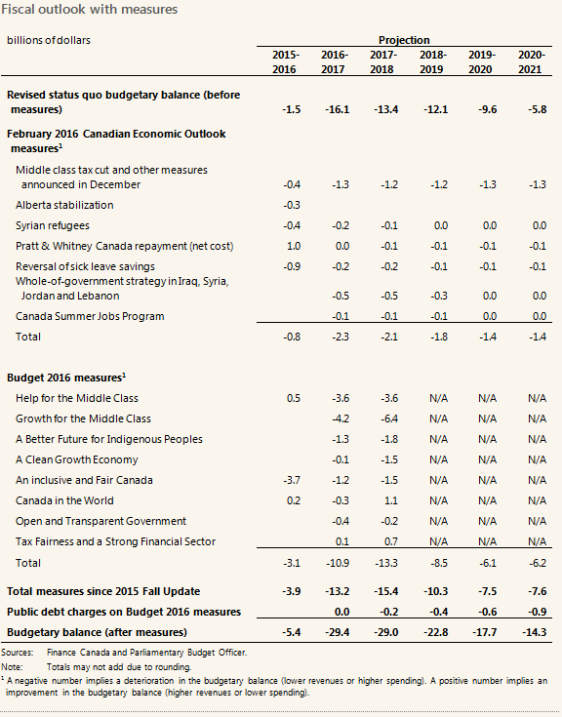

To maintain consistency with past presentation practices, PBO has attempted to compile the standard fiscal planning tables for Budget 2016. However, PBO is unable to provide completed tables due to the lack of information provided in Budget 2016. PBO requested the necessary data from Finance Canada in order to publish completed tables for parliamentarians.

The Government’s adjustment to private sector economic assumptions

Budget 2016 highlights that the use of private sector economic forecasts for fiscal planning “introduces an element of independence in the Government’s fiscal forecast.” However, in Budget 2016, the Government judged it appropriate to lower the private sector forecast of nominal gross domestic product (GDP)—the broadest single measure of the tax base—by $40 billion per year over 2016 to 2020. This forecast adjustment translates into a fiscal impact of $6 billion annually over 2016-17 to 2020-21.

Based on historical experience, PBO believes that the $40 billion per year forecast adjustment to the February 2016 private sector forecast of nominal GDP in 2016 and 2017 is excessive. Indeed, based on the past performance of private sector forecasters, it is likely that the actual outcome for nominal GDP in 2016 and 2017 will exceed the levels used for fiscal planning purposes, resulting in smaller-than-expected budgetary deficits in 2016-17 and 2017‑18, all else being equal.

PBO believes that the Government’s adjustments to the private sector forecast (particularly when the adjustments are excessive and always in the same direction) erode the “element of independence” that is introduced into the fiscal plan by using the average private sector forecast.

PBO is, however, encouraged by the inclusion of alternative growth scenarios in Budget 2016 to gauge the sensitivity of the fiscal track. Budget 2016 also commits the Government to develop alternative growth scenarios and their fiscal implications, communicating the analysis “to Canadians as projections are updated.”

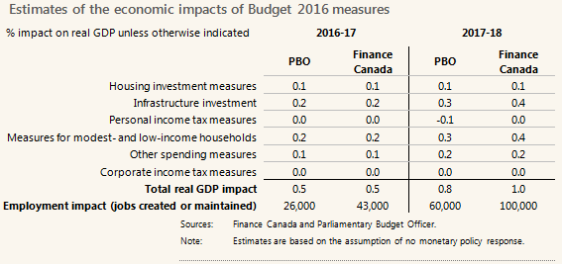

Finance Canada’s estimates of the economic impacts of Budget 2016 measures

Finance Canada has provided estimates of the economic impacts of measures contained in Budget 2016 based on its macroeconomic and fiscal model. However, unlike previous analyses, Finance Canada did not conduct an external assessment of its estimates. For instance, in Budget 2009, to gauge the sensitivitiy of its estimates, Finance Canada asked private sector organizations to calculate comparable fiscal multipliers.

To provide parliamentarians with an independent estimate of the economic impacts of Budget 2016 measures, PBO has used its own macroeconomic and fiscal model. On balance, these estimates are somewhat smaller than Finance Canada’s.

PBO’s estimates assume that measures in Budget 2016 will be implemented as scheduled and as targeted. Aside from the uncertainty surrounding fiscal multiplier estimates, differences in timing (for example by lapsing funds) or in the targeted sector would impact these results.