7 July 2016

FSR 2016 – Clarification and Additional Information

In response to the 29 June 2016 commentary “Why Canada’s long-term fiscal prospects are not a hot mess” by A. Yalnizyan (available at:http://behindthenumbers.ca/2016/06/29/why-canadas-long-term-fiscal-prospects-are-not-a-hot-mess/), this blog post provides clarification and additional information related to our 2016 Fiscal Sustainability Report.

Fiscal sustainability

The concept of sustainability in our reports is based on the government’s (infinite horizon) inter-temporal budget constraint. This constraint requires that the present value of future revenues must equal the present value of future program spending and the current level of debt—the government cannot run a Ponzi scheme where the debt ultimately grows faster than the interest rate.

We would argue that this concept is tied to “affordability” in the sense of income = expenditure. Over time, in present value terms, the stream of revenues (income) must cover the future stream of program spending and the interest on the existing debt (expenditure). If the stream of future revenues does not cover the future stream of program spending and interest on the existing debt, then debt will follow an explosive path and so will debt servicing.

However, to put this concept into practice we use a finite horizon (but over a very long timeframe—75 years) budget constraint and therefore need to make an assumption about the level of debt at the end of the horizon. Based on other studies, we chose to use the level of debt that would be consistent with achieving a debt-to-GDP ratio at the end of the horizon equal to the current level. However, we do not indicate that this is the “right” level. Indeed, this is a technical assumption and we should be more careful to describe it as such.

That said, while this might seem like a crucial assumption, given the length of our time horizon, it really isn’t. Table 8-5 in our report shows our fiscal gap estimates assuming an endpoint debt-to-GDP ratio of 100%. Tripling (almost) the federal debt ratio assumption from 33.7% to 100% increases federal fiscal room from 0.9% of GDP in our baseline estimate to 1.7% of GDP. Tripling (almost) the subnational debt ratio from 32.5% to 100% decreases the fiscal gap from 1.5% of GDP to 1.0% of GDP. Under the alternative debt ratio endpoint assumptions, it is still the case that the federal (subnational) fiscal structure is sustainable (unsustainable). As the commentary rightly notes, this is all about the trajectory of the debt-to-GDP ratio—sustainability simply means that the debt ratio can’t explode over the long term.

Subnational government health spending

The commentary’s description of the approach we take to project subnational health spending is not correct. Note 9 in our report provides a brief description but it probably isn’t sufficiently clear (previous reports provided more detail). Essentially, there are 3 main drivers in our projection of health spending: nominal GDP; “ageing”; and excess cost. We assume that there is a 1:1 relationship between growth in health spending and growth nominal GDP. The ageing component of our projection weights per capita health spending by age group (in 2013) by projected age group shares in the population. So, the first 2 drivers are indeed “forward-looking” and not based on growth rates over the past 30 years.

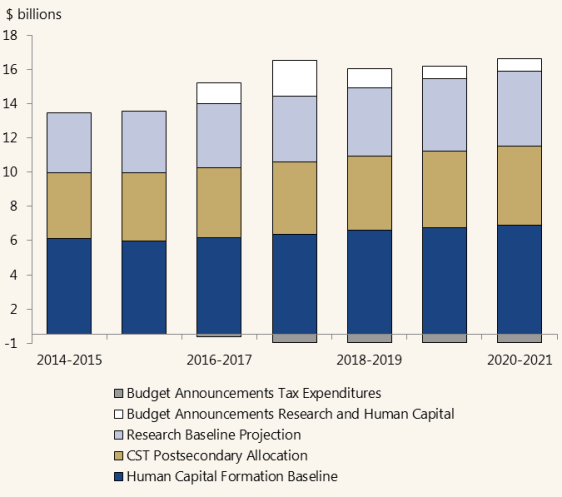

The excess cost component in our projection is, however, based on the average growth observed over 1982-2015. Over the historical period, excess cost is calculated residually—the growth in health care spending that exceeds growth in nominal GDP and “ageing”. In our baseline projection, we do assume that growth in excess cost will be the same as it was, on average, over 1982-2015. Our estimates suggest that there is some mean-reversion in excess cost growth. While excess cost growth has been negative since 2010, it appears to be edging higher, returning to our assumed level (Figure 1). (N.B. The commentary notes that since 2012, “things seem to be changing” with respect to trends in health care spending. While growth in health spending, based on CIHI data, decelerated in 2012 and 2013, CIHI numbers for 2014 and 2015 are CIHI forecasts (which we believe are based on governments’ main estimates/appropriations.)

Figure 1: Excess cost growth in subnational government health spending, 1982-2015 (%)

Sources: Canadian Institute for Health Information; Statistics Canada; and Parliamentary Budget Officer.

Like everyone else, we don’t know what excess cost growth will be over the next 30 years. Mean reversion for excess cost growth seems reasonable to us for a baseline. We do consider an alternative scenario in which excess cost growth is zero (Table 8-4), however, this does not change our conclusion about the (un)sustainability of the subnational sector.

Immigration

By construction, population growth feeds into both our revenue and spending projections.

Over the projection, our assumption about the immigration rate is taken from Statistics Canada’s medium population projection (http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/91-620-x/91-620-x2014001-eng.pdf) and is not simply the average observed over the past 30 years. Indeed, our assumption is very close to recent immigration rates (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Immigration rate, 1971-2014

Sources: Statistics Canada and Parliamentary Budget Officer.

Sources: Statistics Canada and Parliamentary Budget Officer.

Moreover, in our sensitivity analysis, we do consider a younger or “lower cost” population projection where the immigration rate is 9 immigrants per 1,000 persons (compared to 7.5 in our baseline). Under the lower cost population scenario, federal fiscal room increases from 0.9% to 1.3% of GDP and the subnational fiscal gap falls from 1.5% to 1.1% of gap (Table 8-1). However, our conclusion about federal and subnational sustainability is not changed under this alternative scenario.

Related posts

-

28 June 2016

This report extends PBO’s medium-term analysis to assess the fiscal sustainability of Canada’s federal government, subnational governments and public pension plans.

Source: Fiscal Sustaintability Report 2016 – Clarification and Additional Information