MAY 05, 2016 by Press Progress

Apparently when the Fraser Institute hears “child care,” they seem to think about sending young adults off to university.

When most Canadians hear “child care,” they probably picture toddlers in daycare.

But when the Fraser Institute hears “child care,” they seem to think about sending young adults off to college or university.

In their latest report examining “child care in Canada,” the right-wing think tank sets out to calculate just how much money Canada spends on child care every year.

But a closer look at how they came up with their numbers shows a few interesting surprises!

What surprises?

Well, although the cover of the report features a photo of a tiny infant struggling with a set of building blocks, the report itself says it counts saving for university as a “child care” cost.

In calculating child care costs in Canada, the Fraser Institute includes the $800 million Canada Education Savings Grant program that the report itself describes as something designed to help parents “save for their child’s post-secondary education.”

Which only begs the question: is it reasonable to include the cost of saving for college or university as a “child care” program?

The Fraser Institute has a few other “child care” costs that may stretch the definition of “child care”:

• The former Conservative government’s Children’s Fitness Tax Credit, eliminated in the Liberal government’s 2016 budget, which deducted up to $150 for kids under 16 involved in organized sports. Canada Revenue Agency said that includes “strenuous games like hockey or soccer, activities such as golf lessons, horseback riding, sailing and bowling.”

• The Canada Child Tax Benefit, a means-tested grant aimed at lower-income families to “help them with the cost of raising children under 18 years of age” – although it’s a direct-payment that is not explicitly tied to child care costs.

• The former Conservative government’s Universal Child Care Benefit, also eliminated in the 2016 budget, which was a direct-payment of between $100 to $160 per month for everyone under the age of 18 – it too was not explicitly tied to child care costs.

The Fraser Institute includes all of these in their estimate of what Canada spends on child care.

If any of this seems a bit off from what most Canadians think when they hear “child care,” the Fraser Institute has an explanation:

“It is important to explain the distinction between child care and daycare as those terms are used in public policy discussions in Canada. Child care is the broader term and encompasses a range of services and benefits that flow to children. It includes daycare programs, but also covers cash benefits flowing to families to assist them with raising their children.”

But it’s not clear whose “distinction” that is, though.

A 2014 Statistics Canada report on child care limited their scope to “nannies, home daycares, daycare centres, preschool programs and before and after school services.”

Quebec’s government defines child care programs as “childcare centres, private day care centres and home childcare services.”

Meanwhile, Canada Revenue Agency defines a “child care expense” as any amount you pay “to have someone look after an eligible child” under the age of 16 because you have to work or go to school.

Saving for university or subsidizing a teenager’s sporting activities are also notably absent from “discussions” about “child care” here, here, here, here, here and here.

What’s else? One of the citations hiding at the end of the report pegs child care costs in Canada about $20 billion lower than the Fraser Institute’s own estimate.

$20 billion is roughly the amount the Fraser Institute’s report pegs as the combined cost of the CESG, CCTB and UCCB.

That might not be a big surprise.

The right-wing Institute’s annual reports on how much average Canadians pay in taxes have also been criticized for including things that average Canadians don’t actually see on their tax bills, like corporate taxes and oil and gas royalties.

As the former editor of The Walrus John MacFarlane once noted:

“Critics of the Fraser Institute report have also pointed to a bias in its definition of taxes, in terms of what it included in its calculation of the average tax bill. Are royalties on oil and gas revenues taxes? Are import duties taxes? Are taxes on goods and services, property, vehicles, fuel, alcohol, and tobacco — so-called consumption taxes — as burdensome as those applied to income? Is it reasonable to include corporate taxes in the total that Canadian families pay?”

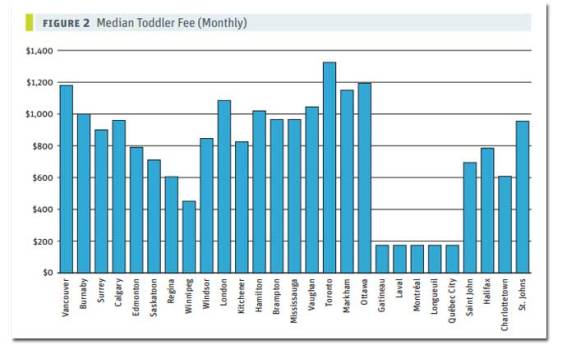

But despite what the Fraser Institute thinks, in reality, child care costs for Canadian families who actually have young children to worry about are still out of control:

Photo: robtowneo. Used under Creative Commons license. Shutterstock.

Source: Fraser Institute thinks sending your kid to university counts as “child care”