Investigations show that unique compounds in cranberry juice, dried cranberries and various cranberry extracts hold great potential for the entire body.

CARVER, Mass., July 19, 2016 /PRNewswire/ — While decades of cranberry research has found that regular consumption of cranberry products promotes urinary tract health, leading scientists studying the bioactive components of fruits and other foods reported that cranberries possess whole body health benefits.

In a July 2016 Advances in Nutrition supplement, Impact of Cranberries on Gut Microbiota and Cardiometabolic Health: Proceedings of the Cranberry Health Research Conference 2015, a team of international researchers reviewed the complex, synergistic actions of compounds that are uniquely cranberry. Their discussion led them to conclude that this berry may be more than just a tart and tangy fruit.

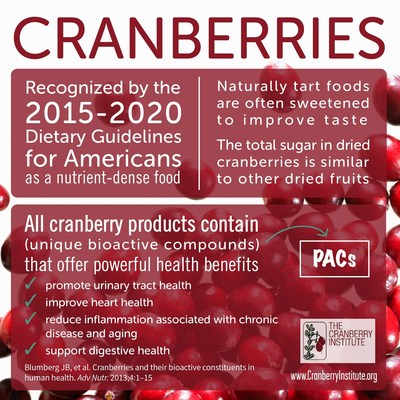

“It has been established that cranberries rank high among the berry fruits that are rich in health-promoting polyphenols,” notes lead author, Jeffrey Blumberg, PhD, of the Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging at Tufts University in Boston, MA.

“But now, recent investigations have shown that the cranberry polyphenols may interact with other bioactive compounds in cranberries that could protect the gut microbiota, and provide antioxidant and anti-inflammatory functions that benefit the cardiovascular system, metabolism and immune function.”

Recognition of the important role gut microorganisms play in human health has gained attention of scientists, reaching all the way up to the White House with the National Microbiome Initiative.

Emerging evidence has found that the gut microbiome may impact the health of the immune system and brain, as well as how the body balances energy and uses carbohydrates and fat.

Preliminary investigations with cranberries, some of which were performed in animal models, have revealed that cranberry bioactives show promise in helping to strengthen the gut defense system and protect against infection.

The effect of cranberry products on cardiovascular health and glucose management was also explained in the review. Authors of the paper described promising links between cranberry products and blood pressure, blood flow and blood lipids.

One study identified a potential benefit for glucose management with low-calorie cranberry juice and unsweetened dried cranberries for people living with type 2 diabetes. Benefits for heart health and diabetes management have been attributed to the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of the polyphenols in cranberries.

Given the wide range of ways to consume cranberries – juice, fresh, sauce, dried, or as an extract in beverages or supplements – additional human studies will help determine all the ways that cranberries may influence health.

The scientific community and the cranberry industry agree – the impressive potential that cranberry bioactives may have on public health is worthy of further exploration.

“The bioactives in cranberry juice, dried cranberries and a variety of other cranberry sources have been shown to promote an array of beneficial health effects,” explains Dr. Blumberg.

“Given the complex nature and diversity of compounds found in berry fruits and how they interact with each other, I believe we have only scratched the surface when it comes to identifying the potential power of the cranberry.”

To read the proceedings in their entirety, the Advances in Nutrition supplement can be accessed here: Impact of Cranberries on Gut Microbiota and Cardiometabolic Health: Proceedings of the Cranberry Health Research Conference 2015.

Source: Scientists Agree that Cranberry Benefits May Extend to the Gut, Heart, Immune System and Brain