Three years ago, Olga Borisova decided to join the St. Petersburg police force. Eighteen years old and, by her own description, a petite, fashionable young woman, she wasn’t your average cadet.

After a little more than a year, she quit, and has since become an active member of the Russian democratic opposition.

Earlier this month, Borisova wrote for the website Batenka.ru about her experiences as a police officer.

RuNet Echo is publishing her text, translated into English, in three parts. This is the first installment. You can read her full story here in Russian.

“Remember, you don’t have holidays. Holidays aren’t for the police.”

They gave me a uniform, and I stopped coming to work dressed in new Reeboks and a pink jacket. My dad drove me to the warehouse where I was issued my uniform. I’d never have been able to carry back home all those things myself. It was all on iron hangers that were ice-cold to the touch.

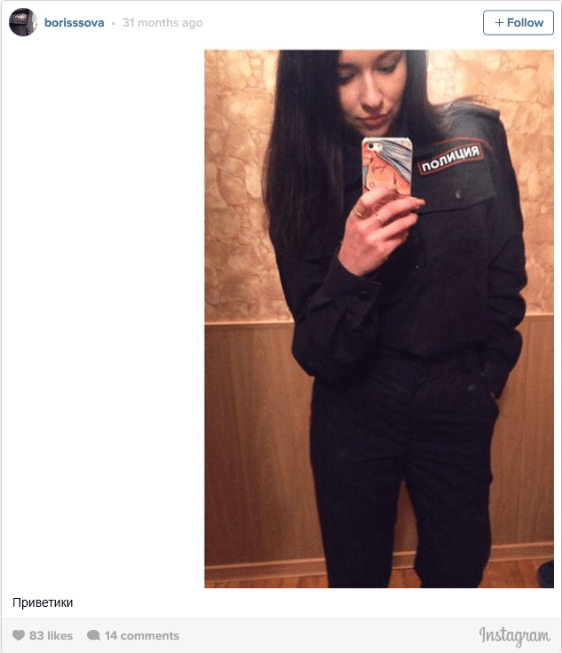

There was a parade uniform, a winter uniform, and a summer uniform. Dark blue. My favorite color. I ended up having to buy a lot myself at the commissary. (They didn’t make an extra small for police officers.) I brought it all home. I tried on the “vole”—the patrol-guard uniform: a dark-blue shirt, pants, and ankle boots. I took a picture of myself, posted it on Instagram, and wrote, “Hiya.”

“VODKA AND ORANGE JUICE, WELCOME TO THE FORCE, YOUS,” the section commander told me. When someone got their first paycheck, they had to buy everyone drinks.

They called the two-story patrol-guard building “base.” On the first floor, there was just a watchman. On the second, there were offices and a large hall, where we presented our reports about completed assignments. There was also a rec room with a green leather couch and a refrigerator. People brought oatmeal and purée from home. The main thing people did there was drink and have all kinds of parties.

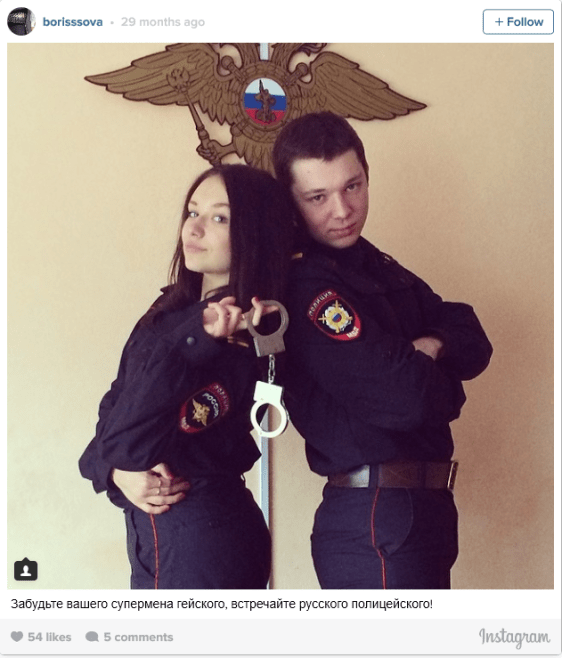

Sergeant Valya used to go around in denim miniskirts and she drank a lot. She was something of an assistant manager there. She gave me my pair of handcuffs, my rubber stick, and my service book. The stick attaches to the belt on your waist, but the stick was so long that it looked pretty ridiculous on someone my height. It almost dragged on the ground. I had to go to the commissary myself and buy one a little shorter.

So I became a junior sergeant. There were two gold bars on my uniform’s shoulder straps. The police academy admits cadets every three months, so you just start working, if you’ve finished basic training, but admission isn’t yet underway.

When you’re just starting out, you’re very shy. A representative of law enforcement should, I thought, display a certain severity. But I didn’t have it.

“Police Junior Sergeant Borisova, your documents,” my partner Andrei would say, teaching me how to address people. “Now your turn. You’ll get it.” I imagined that I was playing some role.

“OLYA, YOU’RE A COP. YOU’RE A COP,” I told myself, and maybe thanks to some experience in theater, it worked.

“You are committing an administrative offense,” I said as confidently as possible, moving on to the next happy group of people drinking beer in the subway.

You’ve got to grasp that you have the right to demand things legally; you have the right to detain people. Now you are a representative of the authorities. Time passes and you get used to it. You start to feel more confident. You feel a duty to “maintain order” not just at work, but in your private life, too.

I wasn’t afraid to walk around outside at night: I knew all the “boys in blue” who were working the various beats, and I knew that at any moment I could call them. I knew that I wouldn’t be without protection.

I think the moment you put on the uniform and feel the authority, that’s when the “professional deformation” starts. They can make you work overtime, and you get used to the idea that you have to do it. You can be standing outside at your post in the rain, feeling like a stray dog, but you keep working, putting up with all of it, because that’s what you’ve got to do.

Patrol officers go down into the subway to warm up.

“I swear to endure the hardships associated with law-enforcement service, to be an honorable, brave, and vigilant member of the force, and to safeguard all state and official secrets.” You knew where you were going.

If you work the day shift, you report to your unit at 7:30 a.m., and change into your cop uniform. Then everyone goes together to headquarters, arriving by 8 a.m., where you retrieve your service weapon. The captain then reads out a summary of the previous night’s patrols, while you take notes in your service book. Overnight, somebody stole a bike, so you write down the color, the bike’s model and series, the full name of the person who filed the police report, and the case number. Then everyone is dismissed, and you head for your station, or your beat. You can take lunch whenever. When you take lunch, you jump on the radio and tell the other on-duty officers. Every police station is linked to its own routes and there are clear boundaries.

Finally, you make it to your precinct. There it is—your territory where you’ve been charged with maintaining the public order.

Then some drunk in custody, or better yet a minor brought into the station because he was caught smoking in school, walks up and says, “Cops are shit. You should all be burned.”

I can’t even count how many times I heard people tell me, “Hey you, bitch, you got nothing better to do?”

If you work “on the ground” (meaning, if you’re working outside), you represent the police and are its very face. From talking to you, people will form their opinions about law enforcement. And I liked being an exception for some people. I was never rude to people in police custody, even when they said to my face that I should be set on fire for being a cop.

Sometimes, you stand outside in the rain for 14 hours, and then you go inside a store to get warm, because you’ve lost feeling in your hands and your nose from the cold. You’re ready to curse everything to hell, but then somebody smiles at you, and thanks you for helping them with directions to some place. And things become easier again.

We would go into the subway to warm up, rubbing the blood back into our feet, while sitting on the stairs, like a bunch of bums. I didn’t have any children waiting for me back home, but those who did explained that their mom or their dad had the same kind of work.

On New Year’s, May Day, International Women’s Day, yes and even the Day of the Police, I was working at the station. In moments like that, you remember why you took the job. You remember what it’s all for. And it’s not the uniform, or the ability to make “lawful demands” of people. It sounds corny, but the truth is that I was there because it brought me pleasure to help people.

I drank a lot of Nescafe “3-in-1” coffees and ate a lot of muffins. There was a little store that had pastries just outside my precinct, which was tucked away in a typical Petersburg courtyard.

Nearby there was a subway station that was a big thoroughfare for people—especially non-locals. In the middle of the day, guys would often come around and park somewhere around the corner and start “earning some dough.” They’d check the documents of anybody who didn’t look Slavic. If they saw anything that looked fake, they put the person in the back of their patrol car.

“No sweat, buddy. Now you’re going home. Where ya from? Tajikistan? Wanna go home? No? Well what are we gonna do, then? You got any suggestions?”

Later, one of these “cops” told me, “My little Marina has a bday coming up, and I’ve got to get her something, but payday isn’t anytime soon.” They thought Andrei, my older partner, who never took any bribes, was simply no good at the job.

You’ve probably never seen how cops cry.

With every day on the force, I came to realize that there was even less justice within the police than there is on the streets. I saw how they abuse both the honest and the dishonest cops simply “because they could.” It was a display of intoxicating power. It’s the opposite of how they lure you in, and smile so you’ll stay. There aren’t enough staff, they say. “There’s a shortage.” Someone is on vacation leave. Another person is taking sick time. Somebody’s on maternity leave.

The head of my unit was a 27-year-old senior lieutenant who we called “Sweetie.” He had this nickname on Vkontakte and among the staff sergeants, who all hated him. I heard a story about how, just a few months after his son was born, he burst into a bordello completely drunk, and lost all his documents in the mess. Afterwards, Sweetie started to “jerk me off”—that’s a term in the police. It means he started criticizing everything I did.

Once, after a station inspection, he ripped into me about the loose stitching on my service book. (Issuing stitched service books, incidentally, is the sergeant major’s job.) He claimed that I undid the threading myself. Then he left, and I went out back with a colleague and started crying, not understanding why he was yelling at me.

After one of these encounters, I called the senior lieutenant a piece of shit in the presence of his assistant. Naturally, he reported me. And that evening I got a phone call from a not-very-sober senior lieutenant, who was trying to understand why he was a piece of shit. I told him that I didn’t understand why he behaved the way he did. “You’re not supposed to understand anything,” he answered. “You’re supposed to take orders.”

“Why have you detained so few people?”

“Because there’s no quota system in Russia.”

For an answer like that, they’ll cite you for a broken locker in the next inspection, and the next thing you know a report is sitting on the senior lieutenant’s desk. A couple of reports like that, and it’s “goodbye, duty to the Motherland.” Because there’s no quota system in Russia.

Other than the usual arrests, like detaining somebody in the subway for walking around with an open can of beer, there was one time I took part in a controlled purchase. It was a methadone prostitute named Katya with a decent sense of humor. We moved in and detained her just as she dug out the “stash.” Then she decided to “phone a friend” [and snitch on her supplier]. She didn’t do any time, and a couple of months later her kidneys gave out and she died.

There was also one time when we rescued an elderly sick woman who’d fallen out of her walker and lost consciousness inside her locked apartment.

And there was another time when we responded to a fire alarm, cordoning off a building. They evacuated the burning building, and it was our job to make sure that nobody got past the police tape. Don’t let anybody in, where it’s dangerous. I saw a woman begging to be let across. She was nearly blind, and she kept crying, “My dog is still in there. I need to go back for her.” She started writhing around hysterically, and begging on her knees. We needed to calm her down, so I decided to find out what kind of dog it was. It turns out it was a dachshund—a brown one. So I went inside behind the tape and Tanya the scared dachshund lept into my arms, and I returned her to her owner.

There was one time we couldn’t save a man. He’d taken out a big loan for his business, and then he couldn’t pay it back. He wrote a note and went out onto the stairwell balcony, hopping the fence. We tried to talk him down “from below” with a megaphone. I wasn’t there, but I followed it on the radio. I listened to a conversation between two on-duty officers:

“So what’s going on over there?”

“We’re talking.”

“Got it.”

Twenty minutes later, I heard this:

“Now what’s going on?”

“He jumped.”

His wife is still paying off his debts. In the police report, his suicide was recorded as “fell from a great height.”

![]() Written by Olga Borisova

Written by Olga Borisova