Get the report

Household Indebtedness and Financial Vulnerability.pdf

Get the data

Figures_Data.xlsx

Summary

This report reviews the evolution of household indebtedness in Canada and assesses prospects for household financial vulnerability over the medium term. The assessment, however, is based on financial indicators that represent economy-wide averages, which can mask wide variation across households. An assessment of financial vulnerability based on household microdata is beyond the scope of this report.

The indebtedness of Canadian households continues to trend higher. In the third quarter of 2015, total household debt (i.e., credit market debt plus trade payables) reached 171 per cent of disposable income. In other words, for every $100 of disposable income, households had debt obligations of $171. This is the highest level recorded since 1990.

- Among G7 countries, Canada has experienced the largest increase in household debt relative to income since 2000. Households in Canada have become more indebted than any other G7 country over recent history.

- Measured relative to household assets, household debt has moderated in recent years. In the third quarter of 2015, household debt accounted for 17.0 per cent of household assets. But this was still above the average of 15.4 per cent prior to the global financial crisis.

- Analysis conducted at the Bank of Canada suggests that low interest rates, higher house prices and financial innovation have contributed to the increase in household indebtedness.

Policymakers continue to express concern about the vulnerability of households to economic shocks, such as unexpected job loss or higher-than-expected interest rates. While the household debt-to-income ratio provides an indication of household indebtedness and facilitates international comparisons, it provides a limited measure of household financial vulnerability.

What matters more for financial vulnerability is not so much the level of the debt relative to income, but rather the capacity of households to meet their debt service obligations. A financially vulnerable household is one that is required to devote a substantial portion of its income to service its debt. It faces greater exposure to negative income and interest rate shocks, and is more likely to be delinquent in its debt payments.

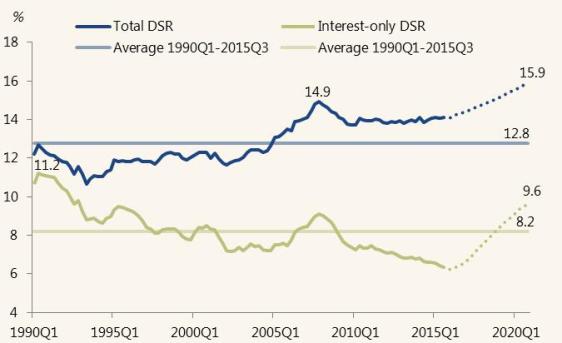

Financial vulnerability is typically measured by the debt service ratio (DSR), that is, household debt payments expressed relative to disposable income. In this report, we adopt Statistics Canada’s concept and measure of obligated debt payments, which includes required principal and interest payments, but excludes debt prepayments.

Based on PBO’s November 2015 Economic and Fiscal Outlook, we project that household debt will continue to rise, reaching 174 per cent of disposable income in late 2016, before returning close to current levels by the end of 2020.

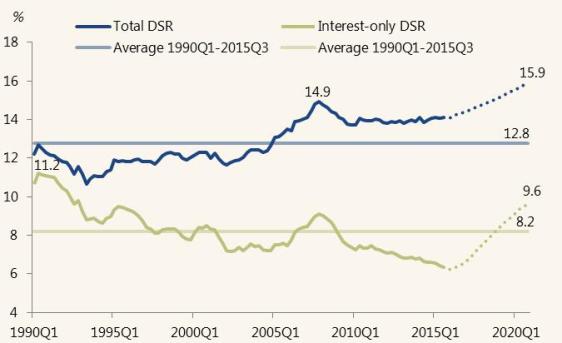

Household debt-servicing capacity will become stretched further as interest rates rise to “normal” levels over the next five years. By the end of 2020, the total household DSR, that is principal plus interest, is projected to increase from 14.1 per cent of disposable income in the third quarter of 2015 to 15.9 per cent.

Household debt service ratios

Based on PBO’s projection, the financial vulnerability of the average household would rise to levels beyond historical experience.

- The projected increase in the total DSR to 15.9 per cent would be 3.1 percentage points above the long-term historical average of 12.8 per cent (from 1990Q1 to 2015Q3). It would also be almost one full percentage point above its highest level over the past 25 years, 14.9 per cent, which was reached in 2007Q4.

Analysis conducted at the Bank of Canada (see Djoudad (2012)) indicates that an increase in the DSR “would imply that households are more vulnerable to negative shocks to income or to interest rates, making household balance sheets more precarious and having a negative impact on financial institutions”.